Return to Course

Victorian Era

Victorian Culture:

The Victorian Era was shaped by international cultural, political, and economic forces:

- Imperialism

- Industrialism

- Slavery and Abolition

- Emergence of the Nation State

- Development of Democracy

However, Queen Victoria is an apt symbol for most of these Victorian tendencies.

"Portrait of Queen Victoria." (1859). Franz Xavier. Painting. Great Britain.

Queen of England and Empress of the United Kingdom, Victoria reigned from 1837 - 1901.

During Queen Victoria's reign:

- The industrial revolution grew at an exponential rate.

- Slavery reached its zenith and was abolished in the Americas (including British colonies).

- Nationalism grew in the ntion-states that formed after the Napoleonic Wars in Europe.

- England grew from a kingdom to a world empire.

Imperialism is the force that magnified the effect of Victoria's reign, as the Horrible Histories clip illustrates below.

Imperialism

http://vimeo.com/102970407

Industry

Eighteenth-Century: French Court Fashion

- How does this dress construct the female body?

- How does this dress transform the female body into an icon of political power?

Court Dress 1780s (France)

During the Victorian Era, women's court fashions became the fashions of the public, fueled by the industrial revolution. By contrast, men's fashions became more practical (in fact, it was the last major change for men's fashion in the modern world).

Thus, the Victorian Era was marked by the construction of gender through clothing that was mass-produced by the industrial era.

Fashioning Gender Identity in Eighteenth-Century Clothing

Can you tell which of these details is for a woman's outfit and which is for a man?

Men's and Women's Suits ca 1780-1790

As the fashions of the aristocratic elite were adopted by the emerging middle class, their inherent gender ambiguity was criticized. Periodicals such as The Tatler and The Spectator helped transform aristocratic fashions for the increasingly polarized social spheres of men and women. Men's clothing became increasingly austere and functional while women's fashions continued to function as status symbols and embrace the extravagance that characterized eighteenth-century aristocratic clothing.

The 1790s: Revolution in Fashion

During the 1790s and the first decades of the 1800s, women's fashions changed dramatically.

Woman's Day Gown ca. 1800

The simple, high-waisted shifts of worn from 1790 - 1810 resemble the UNDERCLOTHES of earlier decades. These dresses were truly "revolutionary" - keeping in step with the political and social movements of the 1790s.

Corset, panniers, and Chemise (ca. 1760-1770).

However, these changes in women's fashions were as short lived. By the 1820s, simple shifts were again regulated to the role of underwear. Industrialization, the expanding wealth of the middle class, and the goading of fashion magazines created an elaborate culture of women's fashion.

Corset, Chemise, and Draws ca. 1830

The Rise of Corsets and Crinolines: Constructing the Nineteenth-Century Female Body

During the 1800s, woman's body was literally shaped by the clothing (and devices) she wore. Her clothing indicated her place in the social hierarchy as well as her mastery of current etiquette. During the nineteenth-century, the full skirts and constricted waists of the eighteenth-century court culture permeated the middle class.

Women's fashion was characterized by the CORSET, petticoat, and CRINOLINE.

This page shows the evolution of female silhouette throughout the nineteenth-century. How does the fashion of men's clothing change throughout the century? What is the significance of this difference for nineteenth-century culture?

Day Dress, ca 1820

Notice the expanding figure of female fashion - this dress requires a corset and petticoats.

By the middle of the century women need a corset and hoop skirt to create the desired fashion.

Day Dress, 1860.

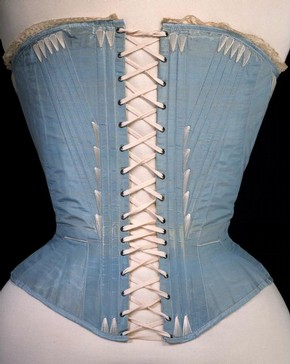

CORSETS:

Corsets were an ESSENTIAL part of a woman's attire. Some medical experts in the nineteenth-century claimed that the corset compensated for a woman's natural deficiencies (they claimed that a woman's spine was too weak to support her body, especially after puberty, and a corset was necessary to give her the support she needed to stand upright).

How do advertisements like this position the women's fashion with power matrices?

These corsets are a part of the fashion exhibit in the Victorian and Albert Museum in London.

Corsets were generally worn from the age of twelve, onwards. These restrictive devices could actually compress a woman's ribcage, causing permanent damage. However, women who did not wear corsets were immediately labeled "loose" women. Furthermore, the corset was thought to impose MORALITY upon the unruly (sexual) female body, curbing the appetites that resided in the torso and mid-section (See

"Crinolines, Crinolettes, Bustles and Corsests from 1860-80").

This photograph from the 1890s features a woman who has tight-laced her corset to achieve what is referred to as a WASP WAIST. However, this extreme was the exception rather than the rule.

HOOP SKIRTS AND CRINOLINES:

The hoop skirt came BACK into fashion in the 1850s (just after Frankenstein). The hoop skirt, combined with the corset, emphasized a woman's ARTIFICIALLY TINY waist and accentuated her bust and hips (her figure - her sexuality).

Evening Dress (ca 1860)

This evening dress utilizes a crinoline and a corset rather than a hoop.

Cage Crinoline (ça 1870)

Rigid hoop skirts were replaced by the more flexible crinoline cage in the later-decades of the nineteenth-century.

The hoop skirt or crinoline, combined with the corset, forced women to (outwardly) conform to mid-nineteenth-century ideals of feminine passivity because these two devices effectually rendered women unable to engage in (meaningful) physical activity.

- Corsets restricted breathing, effectively stopping women from engaging in strenuous (or normal) physical activities.

- A tight corset forced women to take shallow breaths (creating the sexually alluring "heaving bodice" effect)/

- Wearing a corset for a prolonged period of time (since age twelve) forced the ribcage to conform to an UNNATURAL hour-glass form that could be life-threating, especially during childbirth.

- Hoop skirts hampered any sort of movement, surrounding women in a (barely) mobile cage of wire, cloth, and crinoline. Even movement within the domestic sphere was very difficult (as the cartoon below states).

- Hoop skirts and crinolines were more than a nuisance, they were a FIRE HAZARD. Some estimate that the second leading cause of death among women (in the West in the nineteenth century) was FIRE (burns). Cloth was ESPECIALLY flammable in this era and big skirts were FREQUENTLY catching fire. Even if women refrained from working in the kitchen (genteel British women were supposed to supervise the kitchen, not work in it), they were constantly surrounded by fire and their skirts were often ignited. Since women's clothing was DESIGNED to be difficult to remove, women could not get free of their burning clothes and they died (often in agony, days later).

This is a nineteenth century cartoon demonstrates that people were COGNIZANT of the annoyance (and irrationality) of fashions (just as we are aware of our own fashion hang-ups).

This illustration shows a woman's crinoline catching on the door of a carriage. While the footman may be laughing at the spectacle, accidents like this could be hazardous (the woman could be caught and dragged behind the carriage, trampled in the busy London street...).

Reception Dress (ca. 1880)

Reception Dress (ca. 1880)

This reception dress from the 1880s relies on a corset and bustle. Women's skirt widths steadily decrease after the middle of the century, but they still require artificial support.

Women's clothing in the nineteenth-century was supposed to serve as a middle-class STATUS symbol. The fashions that denoted the opulence of the aristocracy and upper-class in the 1700s permeated the ever-growing middle-class during the 1800s. Clothing that immobilized a woman demonstrated the wealth of her father or husband, indicating that she had servants and a lady's maid.

Fashions that had been associated with court culture in the eighteenth-century were associated with the nineteenth-century idealization of the middle-class domestic sphere. For example, the fashion plate below is from the Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine. Magazines throughout the nineteenth-century marketed the corse, hoop-skirt, and crinoline to middle-class women.

Creating clothing in the domestic sphere:

This Lozier and Stokes sewing machine advertisement positions women's clothing and the creation of that clothing at the center of the domestic sphere.

Reading Images: Viewing the Female Body in TEXTS

How can we READ images of the female body?

- How do we INTERPRET the images we find?

- How is reading an IMAGE different from reading TEXT?

- How is reading an image SIMILAR to reading a text?

Finding More Material on Material Culture:

Victorian Era Resources

- Victorian Web - this is a resource for everything Victorian.

- Victoria and Albert Museum - this is a resource for primary material, particularly artifacts from the Victorian Era (named for Queen Victoria).

- Secondary Sources:

- RaVon: Romanticism and Victorian on the Net

Comments (5)

Danielle said

at 4:44 pm on Sep 30, 2014

Danielle / Anthony

-vibrant, attention drawing color

-extremely exaggerated "hourglass" figure (wide hips, narrow waist)

-lines of dress draw the eye to center of body

-abundance of floral patterns, overly feminine

-lots of fabric, but still sexual

Eric Mickle said

at 4:44 pm on Sep 30, 2014

The use of the boat as a hat is a symbol for trade.

Orange may be an imported dye so the use of it would imply wealth.

John McCarthy said

at 4:44 pm on Sep 30, 2014

Dress makes hips appear much larger because large hips meant that women were more fertile.

Ship could be seen as a sign of imperialism.

Brighter colors such as orange were harder to produce.

Fan probably came from China.

A lot of embroidery was a status symbol.

London, John, Mitch, Gerrit

Gabriel Stroe said

at 4:44 pm on Sep 30, 2014

The ship represents imperialism, which relates directly to the fan that she's holding. The bright color of the dress makes her noticeable and draws attention. It's regal and bright as opposed to pauper colors.

Nicholas LaFata said

at 4:48 pm on Sep 30, 2014

Nick, Brad, and Celeste.

Big emphasis on wealth, over exaggeration in size. Shows what men had a sexual appetite for this dress has very accentuated curves.

You don't have permission to comment on this page.